Shahu Chhatrapati (26 June 1874-6 May 1922) known as “People’s King” was not just a ruler of the Princely State of Kolhapur, but was a great reformer ahead of his time. Born as Yashwantrao in the Jahagirdar Ghatage family of Kagal, he was adopted by the widow of Chhatrapati Shivaji IV on 17 March 1884 and ascended to the throne on 2 April 1894. At the age of 28 he took revolutionary steps such as introducing 50% reservations for the backward communities in his government jobs when his bureaucracy was dominated by Brahmins and caste Hindus. On 26 July 1902, Shahu Chhatrapati issued a historic document in the gazette of the Karveer (Kolhapur) state. It was a notification in English that reserved 50% of government posts for backward class candidates. Two days later, the England-returned Chhatrapati issued the same notification in Marathi, as was his administrative style. History had been made, as developments that followed confirmed. He had a close connection with Gujarat too: he studied at Rajkumar College, Rajkot and married Lakshmibai, a daughter of Gunajirao Khanwilkar of Baroda. He was proud of considering himself as a Arya Samaji, a follower of a reformist religious organisation established by Swami Dayanand Saraswati who was born in Tankara near Morbi in Gujarat.

Mahatma Phule, a great reformist and educationist, demanded reservations for backward class in a memorandum given to the British Education Commission but could not succeed in making the British accept his demand. It was in 1882, when Jotiba Phule, in his address to the education commission, or the Hunter Commission, demanded that the British purge the education system and public services of the near total dominance of Brahmins. Phule belonged to the Mali caste, a part of the large groupings categorized as Other Backward Classes (OBC). Shahu Maharaj could take the affirmative action for the upliftment of the backwards even when the British rulers in India were hesitant to displease the Brahmins. When he discovered that the non-Brahmin castes and communities did not have enough qualified candidates to claim the reserved jobs, he started a multi-pronged programme to extend free, universal and mandatory education. In 1917, he promulgated an Act making primary education free and mandatory for every child in Kolhapur state. Shahu Chhatrapati began his famous programme to set up hostels exclusively dedicated to particular castes and communities.

“Though the British considered Brahmins as their enemies, they were wary of taking them on since the latter also had a prominent position in the freedom struggle and administration. But Shahu Chhatrapati had this courage. Inspired by Phule and instigated by a particularly nasty incidence of personal humiliation, Shahu Chhatrapati took this revolutionary step in 1902 because he was truly committed to the emancipation of the backward classes," says veteran historian Dr.Jaysingrao Pawar. When Shahu Maharaj ascended the throne in 1894, Brahmins held 67 of the 71 posts (94.37%) in the administrative department of the princely state. In the ruler’s private administration, Brahmins held 46 of the 53 posts (87.79%). The remaining posts in both departments were occupied by non-Brahmins like British officers, Anglo-Indians, Parsis, and Prabhus (upper-caste Hindus). “This was what Shahu Chhatrapati called the Brahmin bureaucracy. He discovered the irony that though this was a Maratha princely state, there were hardly any Maratha (non-Brahmin backward classes, including the Marathas (Patils-Patels), OBCs, untouchables, Muslims, Jains, and Lingayats) in the administration," Pawar explains.

The 1902 document of Shahu Maharaj was an “inspiration" behind Dr. B. R. Ambedkar’s constitutional philosophy of reservation. As such, the ruler of Kolhapur had developed liking for Dr. Ambedkar and supported him financially not only for his studies but also for the magazine “Mooknayak” he launched a century ago. Unfortunately, Shahu Maharaj died in 1922 and Dr. Ambedkar lost a great supporter. That he was much ahead of his time is evidenced by the astounding trajectory and range of the revolutionary and reformist laws/decrees/manifestos he issued. Like the quota manifesto, many of these legislations predated, by several decades, similar laws that the Maharashtra legislature or Parliament passed. Like the Compulsory Primary Education Act of 1917, the Legal Sanction to Inter-caste and Inter-religion Marriage Act of 1919, the Law for Prevention of Cruelty against Women, 1919, and the Manifesto against Observance of Untouchability, 1919.

There are reasons why Rajarshi Shahu Chhatrapati is considered a classic social revolutionary in the reformist tradition of Maharashtra. Ruler of one of the two seats (the other being Satara) of the Maratha empire founded by Chhatrapati Shivaji, he consciously exposed himself to outside influences and especially the modern European ideals of democracy, fraternity and individual liberty. Back home, he interacted with prominent rationalists and reformists like Mahadev Govind Ranade, Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Gopal Ganesh Agarkar. Shahu Chhatrapati travelled extensively in Europe and India, absorbed all that he could, and implemented many of those things in Kolhapur. All India Kurmi (Patels) Mahasabha felicitated him by awarding the title of Rajarshi in 1919 at Kanpur. Reacting to Shahu Maharaj’s 1902 historic document of reservations, Lokmanya Tilak, in his editorials in the Kesari newspaper, called this notification an undiplomatic and immature step and wondered if Shahu Chhatrapati had lost his mind. If this is what Tilak felt, one can imagine the reaction of other Brahmins!

Next Column: Darbar Gopaldas Desai, the forgotten Hero

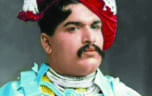

Photo-lines:

Shahu Chhatrapati of Kolhapur